Though overlooked in recent decades, the practices are part of the country’s not-too-distant past, and today, Kazakhstan is working toward exporting its own ecologically “clean†products under its own national brand, Vice Minister of Agriculture Yermek Kosherbayev said during a seminar on supporting the development of organic agriculture and institutional capacity-building in Kazakhstan in Astana on Feb. 27. However, Kosherbayev said, a lack of legislation is slowing the process down.

“Until less than 100 years ago, all Kazakh agriculture was organic,†Ethan Roland, head of the nonprofit Apios Institute of Regenerative Perennial Agriculture based in Massachusetts, told The Astana Times in a Feb. 27 interview. “And it sustained itself for literally thousands of years. … In my opinion, the current ‘development’ of Kazakh (and most other global ‘green revolution’) agriculture towards fossil-fuel-dependent industrial monoculture is highly unsustainable. This alone will drive a shift to more climatically and culturally appropriate agriculture.â€

Moving Away From a Destructive Past

A Nov. 24 roundtable discussion organized by the Astana Centre of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and the ULE Coalition for a Green Economy and the Development of G-Global brought together government, business and nongovernmental organization representatives to discuss the state’s role in supporting organic farming, including providing incentives, as well as specific agricultural technologies.

“The current methods of farming in Kazakhstan are leading to the destruction of natural vegetation that protects the land from erosion and accelerate the process of soil mineralization, which result in drastic decline of its fertility, crops yields and harvest as a whole,†said head of the OSCE’s Astana Centre Natalia Zarudna at the roundtable, as reported by the Times of Central Asia on March 14. Organic farming practices could contribute to solving the problem, she said.

An OSCE report on the discussion said that the group noted that developing organic farming and implementing Kazakhstan’s transition to a green economy depend a great deal on the development of appropriate legislation and government regulation, as well as using domestic and international experience effectively.

Participants called for active policies to stimulate innovation and gain experience and offered 12 concrete recommendations. These included bringing the Ministries of Agriculture and Energy together with the roundtable organizers to draft regulations based on international experience and increase awareness of the green economy transition and organic farming in Kazakhstan; creating an online exhibition of Kazakhstan’s innovative, organic products for EXPO 2017 in Astana; involving Kazakhs more deeply in the organic agriculture category of G-Global’s annual EXPO 2017 competition and passing a draft law on organic agriculture. (The draft law sets out the provision of state support for organic agriculture, including setting rules for labelling organic products from Kazakhstan.)

At a media briefing on March 12, Zhibek Azhibayeva, secretary of the Trade Committee of the Kazakhstan’s National Chamber of Entrepreneurs, said Kazakhstan’s organic products market had been estimated at more than $500 million and that plans were in place to introduce an organic products production chain, the Times of Central Asia reported.

According to Azhibayeva,150,000 hectares of farmland in Kostanai oblast have been certified as eco-friendly. At the Feb. 27 seminar, the Kazakhstan Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (KAZFOAM) reported that 25 farms in Almaty, Kostanai and North Kazakhstan have 296,000 hectares of certified ecologically clean fields.

However, the country’s legacy of environmental damage can be felt today. According to the NP.kz report, the Agriculture Ministry said 21.4 million hectares of land were used for agriculture in 2014, which should be increased to 22.5 million hectares by 2018. However, according to Deputy General director of the Kazakh Research Institute of the Agroindustrial Complex and Rural Development Vladimir Grigoruk, “according to our calculations, it is possible today to grow on only 11.5 million hectares of arable land, as the rest of the area, almost half, is polluted by industrial waste, various chemicals, buried animals or radioactive waste.â€

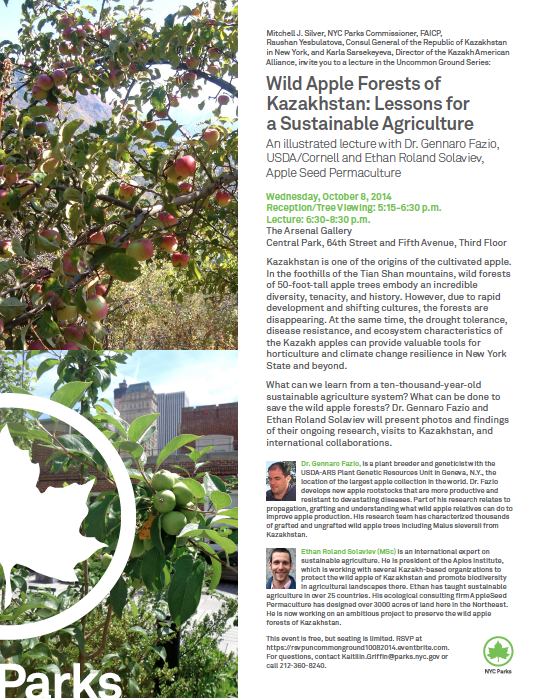

Wild apple forests at site with grapes, hops, licorice, and other economically useful species.

Replanting Organic Roots

Roland is working with the Kazakh Research Institute of Fruit Growing and Viticulture (KazNIIPiV) in Almaty and the Institute for Ecological and Social Development (IESD) in Almaty. They work primarily on preserving and regenerating the biodiversity of Kazakhstan’s apple forests, but also plan to branch out into other areas of biodiverse farming.

“This work is just beginning,†Roland told The Astana Times. “Some of my colleagues … have been working on different aspects of this – e.g. IESD promoting sound agricultural practices within the matrix of the existing biodiverse apple forests. Going forward, we intend to offer workshops on the benefits of biodiverse farming and explore research projects.†He expects to find a receptive audience. His Kazakh colleagues are also enthusiastic about developing organic agriculture, Roland said, especially as its products will likely demand higher prices in local and export markets.

Raul Karychev, laboratory chief at KazNIIPiV, told The Astana Times on March 10 that his institute is studying and implementing elements of organic fruit growing, including identifying varieties most adapted to local conditions and which don’t need chemical treatments and studying adaptive orchard design and crown formation systems, drip irrigation, high-technology farming, organic fertilizer and more.

With international partners including the Apios Institute, the institute has established wild fruit ecosystems in the Zaili Alatau region, Karychev said. He also noted that the Horticulture Master Plan of the Agribusiness 2020 Programme provides for a phased increase in orchard areas in Kazakhstan. “The Kazakh government has embarked on the green economy, so the area of organic orchards and the demand for environmentally friendly products will only grow,†he said.

Wild apple forests, cultivated orchards, overlooking Almaty.

From Wild Apples to Sustainable Traditions

“The wild apple forests of Kazakhstan are part of one of the world’s biodiversity hot spots – it is one of the centers of origins of many fruits, and could potentially hold the keys to a sustainable agriculture of the future,†Roland says. But beyond apples, Kazakhstan also has an important agricultural tradition, and one which is beginning to be recognized and supported.

“Kazakh food production has a fascinating and beautiful history, with two interwoven threads of livestock-focused semi-nomadism and advanced mountainside and outwash valley horticulture,†Roland explained. Now is the time to look back to the country’s early food production methods.

The country’s grasslands and forests would be particularly well-suited to organic and biodiverse agriculture, he said. “Modern ‘organic’ agriculture often does not do much more than change the sprays and offer a bit of focus on soil health. If the overall framework is still industrial-scale tillage, then ‘organic’ alone isn’t much of an improvement.†He proposes instead regenerative agriculture, permaculture and carbon farming.

“In the long term,†Roland said, “I believe that truly sustainable economic and ecological growth will come from Kazakhstan focusing on its ancient agricultural history and incredible resources.â€

These include biodiverse food forests and vast grasslands, which can produce useful yields with little to no input, Roland said. “Mimicking the natural Kazakh ecosystems could produce a new form of mixed perennial agriculture, with many opportunities for unique value-added products.†Among these products could be fruits like pears, plums, peaches and many more; nuts; a variety of berries; vegetables; herbs; honey and maple syrup; plus some smaller livestock. Most of these, Roland said, have been part of Kazakhstan’s indigenous ecosystem for years.

Kazakhstan’s grasslands, if managed holistically, could be systems adaptable enough to withstand changing climates, weather and politics and that could produce enough meat for domestic and export markets, Roland said, sustaining horses, sheep, goats, deer, elk, buffalo and other smaller animals producing cheese, yogurt, kumis, leather and fur.

“The Kazakh people are brilliant and resilient,†Roland concluded. “Despite attempts to crush nomadic culture and massive apple forest biodiversity, Kazakhstan’s ecosystems and organic farmers can hold the key to a sustainable and regenerative future.â€

Maintaining open space and farmland in our towns and cities provides many benefits. Recreational opportunities positively impact people’s emotional and physical health, while contact with trees and living systems has a profound impact on mental well-being. Children who spend more time in “green” settings have reduced symptoms of ADHD and higher test scores. The living systems provide numerous “ecosystem services” such as cleaning the air, infiltrating water and reducing runoff, cooling the community, and bolstering local biodiversity. The land base can also be utilized to grow food and other products to be consumed locally in a way that builds local economic resiliency and improves food security.

Maintaining open space and farmland in our towns and cities provides many benefits. Recreational opportunities positively impact people’s emotional and physical health, while contact with trees and living systems has a profound impact on mental well-being. Children who spend more time in “green” settings have reduced symptoms of ADHD and higher test scores. The living systems provide numerous “ecosystem services” such as cleaning the air, infiltrating water and reducing runoff, cooling the community, and bolstering local biodiversity. The land base can also be utilized to grow food and other products to be consumed locally in a way that builds local economic resiliency and improves food security.